Anniversaries

My personal calendar has annually “repeating events” for birthdays, dates of death, and some other dates for people who are special to me. One such person is T. S. Eliot, and September 26 is his birthday.

So on Monday, I was thinking about Eliot through the day. Four Quartets is, of course, the greatest poetry ever written. (We settled that years ago, back in college, back when we knew how to make decisions. We also decided that King Lear is the greatest play and The Brothers Karamazov the greatest novel. It’s good to have these things settled.) But Eliot wrote much other memorable verse. Towards the end of “The Love-Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” he has a couplet that speaks precisely to the weariness of age:

I grow old . . . I grow old . . .

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

There’s something comic and pathetic in that: an old man’s entire aging process reduced to some rolled-up cuffs on his pants.

---

So I take note of Eliot’s birthday. But how should we refer to it? He was born in 1888, which was 128 years ago. So I’m tempted to say that this is his 128th birthday, even as earlier this year I celebrated, if that’s the word, my 60th. But, Eliot isn’t 128 years old.

Mr. Eliot—he dead.

I could say it’s the 128th anniversary of his birth, even as all of our birthdays that we celebrate are more accurately the anniversaries of our birth. But that’s awkward.

Death’s awkward.

---

Susan and I were married on the feast of St. Michael and All Angels in 1978. So this Thursday, September 29, is the 38th anniversary of our marriage. But it isn’t “our” 38th anniversary. “I, Victor, take thee, Susan, . . . till death do us part.”

I want to speak happily of the day, on the day. I want to say, this is our 38th anniversary, and it was a beautiful day in Santa Fe, September 29, 1978, a lovely fall day, an evening wedding, singing “Christ, the fair glory of the holy angels.” But I can’t say, “This is our 38th anniversary.” It isn’t ours; it isn’t mine either.

Awkward.

---

My calendar also has dates of death. Pious tradition has it that the day a saint died is that saint’s birthday into paradise. For all who die, the time of death is their turning over to God. Often we remember people in our calendar on the day they died. C. S. Lewis, for instance, is remembered on November 22, the date on which he died in 1963. It is a transition that parallels birth: emerging from the confines and relative darkness—the “womb”—of this creation into the more immediate presence of God.

And what then? We do not know, of “those who have gone before us in the faith,” whether they exist in a time that is parallel to ours, whether they are aware of us, whether they are at rest or in growth or being corrected or perfected in other ways. Faith knows the important point, that Jesus takes to himself all who wish to come to him. But of what that means in particular, we remain in ignorance.

It is that ignorance that creates our awkwardness when we think of our ongoing relation to people who have died. How does his life here go on now, there, in that existence beyond death for which we hope?

The awkwardness of this is, I think, authentic and salutary. It reminds us at once of our ongoing connection with the departed, and the mystery of that connection. It turns us, thus, back to God’s gift of hope. In the midst of things that are beyond human comprehension, this side of death, we yet have the divine gift of hope. It is an awkward gift, hope. It is also reality.

---

Out & About. Under this heading I plan to take note of talks, classes, and preaching by yours truly, as well as things in print.

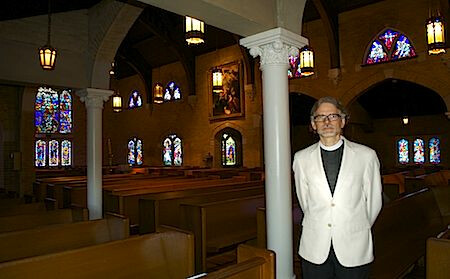

Sunday, October 9, I will be teaching a 10:15 a.m. class on the Giving of the Law. I plan to draw attention to the complex character of law as both gift and sacrifice, making a connection backward from Moses to Abraham at the destruction of the cities of the plain. At Church of the Incarnation, 3966 McKinney, Dallas, in Memorial Chapel.

Sunday, October 9, at 6 p.m., I will be speaking on, and reading from, Losing Susan: Brain Disease, the Priest’s Wife, and the God Who Gives and Takes Away. There will be a reception and book-signing as well. My remarks begin at 6:30. This will be in the education building of Church of the Incarnation, 3966 McKinney, Dallas.

Losing Susan was reviewed in the September 26 issue of National Review, online here (but behind a paywall): https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2016-09-26-0100/victor-lee-austin-losing-susan.