Theology Matters: Why Did Christ Take Our Human Nature?

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made…And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:1-3, 14).

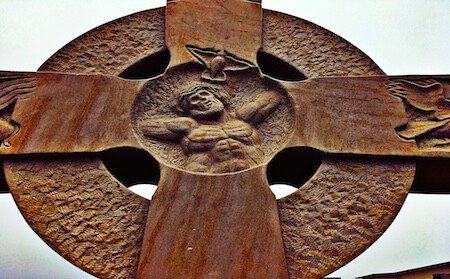

At the heart of the Christian faith is the truth expressed above in St. John’s Gospel – the truth that God the Son became a human being. In doing so, he neither abrogated his eternal divinity nor dissolved his acquired humanity, but was fully God and fully human. And we call this God-man Jesus Christ. It is not for nothing that many Episcopalians, when saying the Creed together, bow low at the words, “By the power of the Holy Spirit, he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary and was made man.” This reverence is the liturgical recognition that the Incarnation – the ‘en-flesh-ment,’ – of Christ is the doctrine on which everything else hinges, including his own Death and Resurrection and, in fact, all of human history. The well-known writer and devout Roman Catholic J. R. R. Tolkien called the Incarnation the “eucatastrophe” of history, that is, a ‘good catastrophe’ – a sudden, singular turn of events that ensures a happy, rather than tragic, ending for God’s creation. And St. John, in his first epistle, even goes so far as to call the denial that Jesus has come in the flesh “the spirit of antichrist” (1 John 4:3). The reason for both is that Christ’s Incarnation makes all his subsequent miracles and mighty works of redemption possible.

But why, one might ask? Why did it have to happen this way? Could not God have found a more fitting way to save humanity from sin and death?

When human beings first disobeyed God millennia ago, they did more than cause offence. God had warned them that the inevitable result of their disobedience would be death, corruption, and separation from him (cf. Genesis 2:17). Repentance would be enough to make restitution for offence given, but it could not heal the corruption that had been contracted like a sickness. Humans become corrupt not just physically, by aging and death, but also spiritually. The first disobedience created a chain reaction, so that humanity as a species gradually descended into more and more destructive behavior toward God and each other.

Since God lovingly created human beings in his image (Genesis 1:26-27) that they may, likewise, be in loving relationship with him, there were two ways he could not respond to the situation. One the one hand, he could not forcibly prevent them from first disobeying him, as that would make free will, and thus true love, impossible. On the other hand, he could not just sit back idly and watch his beloved image-bearers tear themselves apart. What was God to do?

Someone had to neutralize the corruption. Someone had to destroy death by death. And this no mere human could do, being themselves corrupted. Likewise no angel, since they lack the perfection required for a sacrifice as well as the physical body necessary for a physical death. God had the power and perfection to do it, but no physical body. The solution was that God himself – specifically the Word, God the Son – in his infinite love as well as infinite power, would take to himself human nature and unite himself to a human body, born of a Virgin (to show that this was no mere man). As God, he would have the purity necessary to make the sacrifice, and as man he would have the shared humanity necessary to give humans the benefits of that sacrifice. As St. Athanasius, the fourth-century bishop of Alexandria, summarized it so well:

And thus, taking from ours that which is like [that is, human nature], since all were liable to the corruption of death, delivering it over to death on behalf of all, he offered it to the Father, doing this in his love for human beings, so that, on the one hand, with all dying in him the law of corruption concerning human beings might be undone (its power being fully expended on his lordly body and no longer having any ground against similar human beings), and, on the other hand, that as human beings had turned toward corruption he might turn them again to incorruptibility and give them life from death, by making the body his own, and by the grace of the resurrection banishing death from them as straw from the fire.[1]

Thus, Christ, man as well as God, became for us a second Adam, to undo the corruption resulting from the disobedience of the first. In St. Paul’s words, “For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:21-22).

Christ did not hesitate to do what had to be done, to do what had previously been unthinkable – God living and dying as a human being and rising again to life forever. Christ took on our human nature because, as the God who made us, he loved us and did not want to see his beloved creatures destroyed forever. Christ took on our human nature so that our incorruptibility and the image of God might be fully restored. Christ took on our human nature so that, after we die, we might be raised again to immortal glory on the Last Day, as he was on the third day. As St. John witnesses, “we know that when he appears we shall be like him” (1 John 3:2). Thus, as St. Athanasius beautifully put it, Christ took on our human nature so that we might share his divine nature.[2]

[1] Athanasius, On the Incarnation, trans. by John Behr (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011), 57.

[2] Ibid., 107.