Ethiopia and Covid-19

CONVID-19 UPDATE

Trent Pettit, March 23, 2020

My return to Gambella has been delayed because of the outbreak of COVID-19. I am currently under self-quarantine for a couple weeks in Dallas. As of now, it remains uncertain as to how coronavirus will spread throughout Africa. Ethiopia, currently, has only 11 reported cases, though this number is expected to rise. Africa as a whole is not situated to contain the virus quickly when it begins to spread. The Gambella-region is particularly vulnerable because of its position on a very permeable border with South Sudan, which is without a functioning government. Gambella is, however, protected in some ways by heat and a younger population. Ethiopia’s infrastructure is limited and in many areas the doctor-patient ratio is dangerously low (Gambella’s is likely close to South Sudan’s, which is about 1: 60,000[1]). Millions of people in Africa are at risk simply because they remain out of communicative reach and so will not receive information or advanced warning. Returning soon is therefore not possible at this moment. Please join me in prayer for the people of the Gambella region and especially for the students at the college.

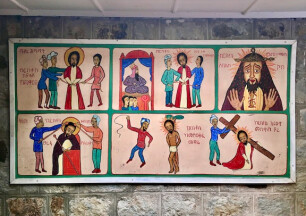

I had hoped to share this video about Gambella as I returned, but I share it with you now as a window into the ministry I hope to return to:

———-

In chapter four of Benedict’s Rule, he tells his monks to “To keep death before one's eyes daily.” We might think that the news alerts we receive on our phones and on t.v. are doing this kind of work for us, but they are not. Benedict’s prescription is part of the “spiritual art” of sanctification that enables the believer to prepare for judgement day, the glorious return of the Lord. Benedict cites 1 Corinthians 2:9 to describe those efforts one must take to “keep watch” over one’s actions, thoughts, and desires such that they might merit the reward God promised us (We can also think of Rom 12:2, 2 Cor 10:5, andPhil 4:8). By no accident the Book of Common Prayer recalls this aspect of the Rulein the Ash Wednesday service: “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return" (BCP, 265). The Scriptural form of Benedict’s Rule and the Ash Wednesday service give us a helpful way to frame the constant updates we are receiving about the global spread of coronavirus. The news on its own cannot tell us how to order our lives in its light. The way that we respond to such news—which includes exercising the recommended precautions—is certainly part of Christian discipleship and witness.

During this time of uncertainty and isolation from one another, I encourage you to take to prayer, especially for those who are especially vulnerable at this time: prisoners, those experiencing homelessness, those in need of addiction-recovery groups (e.g. AA), medical professionals, grocery store clerks, and the elderly. Perhaps this is one of the few means by which we might continue to serve one another and the world amidst social-distancing and mandatory shelter-in-place orders. We can also not stock-pile, exercise financial generosity, and phone our homebound neighbors.

Many of us in wealthy countries that have dependable infrastructure, medical, economic and otherwise, are in this season prone to think as if we live in a kind of “real Lent.” But now we all finally see what has been obscured from our view: the mortal shape of our lives. Indeed, the tone of many has turned apocalyptic amidst this viral threat, and perhaps the instinct to do so should not be too hastily dismissed. For example, consider the destructive nature of world-power economies, especially those of China and the United States, and the air and waterways connected to them that now get to experience what will inevitably be a short-lived sabbath. We will get back to “normal;” the status-quo of industry will be re-cranked with a predictably, economically-anxious fervor. How can God stand it? How dreadfully patient and merciful He has been.

Life’s uncertainty, mortality, is simply what daily experience feels like for most people in the world. That unrelenting sense of vulnerability is made worse exactly by those powers that make our mortality-forgetting “normal” possible. Many aspects of the technologically sustained routines that we so desperately hope to return to are exactly what makes life difficult for so many people. It it also to these that our prayers must turn during our season of “real Lent.”

For those using the first prayerbooks in 16th-17th century England, life’s precariousness was a feature of daily existence that made the annual liturgical recall of our mortality during Lent a coherent existential vesture, exactly because it reminded them of their dependence on the Lord and reaffirmed their hope and desire for our deaths to occur “in Christ.” May this time in self-isolation for those of us in seemingly “Lent-free zones” be a kind of liturgical action that leads us after it, that is, in the light of Easter, into a greater commitment to those communities we take for granted, increase our service to those in need, and embolden our prophetic witness before destructive economic and even medical “Babels” (Gen 11:1-9).

That we exist affirms the we do not belong to ourselves but to God. Our existence is pure gift, one given us by the Father. The creed tells us that we were created along with everything else “through” Christ. We are created by a God that has not abandoned us to suffer fallen existence. He has, rather, joined us in our human estate, which Scripture describes as “taking the form of a slave” (Phil 2:7). The mystery of God’s solidarity with his creatures is expressed in the incarnation by which he shares the experience of being both “wonderfully and fearfully made” (Psalm 139:14). This means that even in times of pestilence and plague, we can be so bold as to claim that God is in control.

We, who are for now blessed with health, may take the occasion that the limits coronavirus imposes on our daily lives to mortify our flesh, receiving the shape of Christ’s life into our mortal lives, including our deaths. Perhaps our Lenten journeys this season might take on the boldness of the Gospel of John’s depiction of Christ’s passion by, in prayer and the re-shaping our lives, we claim Christ’s victory even in the bowels of Sheol. “Keep death always before you,” and be not afraid. “If I say, ‘Surely the darkness will cover me, and the light around me turn to night,’ darkness is not dark to thee, O Lord; the night is as bright as the day; darkness and light to thee are both alike” (Psalm 139:10, 11).

——-

Almighty God, who sees that we have no power in our selves to help ourselves; Keep us both outwardly in our bodies, and inwardly in our souls; that we may be defended from all adversities which may happen to the body, and from all evil thoughts which may assault and hurt the soul, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. (Collect for the Second Sunday in Lent, BCP, 1662)