Giving Up My Rights

Sunday, 13 September 2020: Matthew 18:21-35

21 Then Peter came and said to [Jesus], “Lord, if another member of the church sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?” 22 Jesus said to him, “Not seven times, but I tell you, seventy-seven times. 23 “For this reason the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who wished to settle accounts with his slaves. 24 When he began the reckoning, one who owed him ten thousand talents was brought to him; 25 and, as he could not pay, his lord ordered him to be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, and payment to be made. 26 So the slave fell on his knees before him, saying, ‘Have patience with me, and I will pay you everything.’ 27 And out of pity for him, the lord of that slave released him and forgave him the debt. 28 But that same slave, as he went out, came upon one of his fellow slaves who owed him a hundred denarii; and seizing him by the throat, he said, ‘Pay what you owe.’ 29 Then his fellow slave fell down and pleaded with him, ‘Have patience with me, and I will pay you.’ 30 But he refused; then he went and threw him into prison until he would pay the debt. 31 When his fellow slaves saw what had happened, they were greatly distressed, and they went and reported to their lord all that had taken place. 32 Then his lord summoned him and said to him, ‘You wicked slave! I forgave you all that debt because you pleaded with me. 33 Should you not have had mercy on your fellow slave, as I had mercy on you?’ 34 And in anger his lord handed him over to be tortured until he would pay his entire debt. 35 So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart.”

Today’s Gospel reading continues the conversation and teaching about restoring harmony in the Church, the community tasked with the mission of reconciliation to the world, when peace has been lost due to its members offending and even scandalizing one another. After all, how can the Church work for Christ in the restoration of unity between God and people and with one another if we are at enmity with one another? How can God’s people serve as instruments of unity when we ourselves are divided? The action of forgiveness now takes center stage as a crucial step in the process of reconciliation and restoration. How are we to understand forgiveness then? I know it is not the same as forgetting and sometimes is a gradual process. There is a helpful definition from an anonymous source that has stayed with me over the years: “Forgiveness is me giving up my right to hurt you for hurting me.”

Peter appears to be interested primarily in the limits of forgiveness, what he must do to get by. How many times is one obliged to forgive another’s offenses? Peter wants to do the right thing and most likely thinks his proposal of forgiving seven times is a generous offer, so he must have been surprised by Jesus’ response: “Not seven times, but I tell you, seventy-seven times” (Matt. 18:22). In other words, there are no limits to our obligation to forgive. I am reminded of others, including myself, who like Peter are prone to the human tendency to rationalize our behaviors and are interested in the minimums of what we must do to get by.

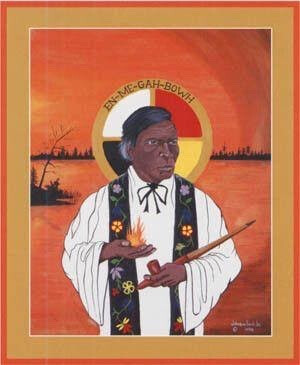

It was my privilege to serve for ten years as the vicar of St. Columba of Iona Church on the White Earth Nation in northwestern Minnesota. St. Columba’s is an historic congregation founded in 1852 by missionary James Lloyd Breck and Enmegahbowh, the first Native American priest in the Episcopal Church. One story that is told of Enmegahbowh is about a time when a man insulted Enmegahbowh’s wife, Biwabikogeshigequay. It seems that Enmegahbowh was torn between Jesus’ injunction to “turn the other cheek” (Matt. 5:39) and defending his wife’s honor. In the end, he held the man down so that his wife could kick him!

My sympathies are certainly with Enmegahbowh’s moral dilemma and the justification of his behavior, but there are more serious rationalizations in the story Jesus tells about “the unforgiving servant.” Human nature being what it is, it is not difficult to identify with the servant in Jesus’ story who was forgiven a debt by the king of millions of dollars! After all, the king could afford to do without that money for he was the richest person in the land. The servant, on the other hand, worked hard for a living and could not afford to forgive a one-hundred-dollar debt. After all, he had a family to feed, clothe, shelter, and send to school. He was barely squeaking by. He really needed the money.

That is usually the way rationalization works. Justification of our actions is an easy trap into which to fall, but if the king in the story represents God, forgiveness becomes a profoundly serious matter in our lives to consider. The Lord’s Prayer expresses the same concept when we pray to the Father: “Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” In the same vein of thought, Jesus also goes on to say: “For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you; but if you do not forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses” (Matt. 6:12;14-15). It sounds like this is more than a good idea and something God demands of us. Yes, if God forgives us the debt we owe to Holy One, then it appears to be a divine expectation that we in turn forgive the debts others owe to us.

Clearly, forgiveness is not an easy task and sometimes feels like an impossibility, but God is on our side in this work. Even a forced willingness-to-begin-to-get-ready-to-think-about forgiving provides a space for God’s assistance and grace. As difficult as it is to forgive others for their wrongs against us, it is a responsibility given us by God to fulfill. If we neglect it, we just might find ourselves on the outside looking in. Today is a good day, then, to ask: “How has God shown me mercy and forgiveness?” and “What debts of mine has God cancelled?” so “Who do I need to give up my right to hurt because they hurt me?”

Michael G. Smith, OblSB, is a bishop of the Episcopal Church, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, and holds a doctorate in preaching.