Candlelit Advent Lessons and Carols at All Saints Cathedral, Cairo

As I’m sure you know, Christmas is not a Muslim holiday; so how does one notice the holiday season in Egypt? It doesn’t snow here; well, not usually. It did snow in Alexandria this week. Christmas trees and Christmas decorations are a rare sight, but some churches have them and even the inventory at the historic churches’ bazaar’s are changed into a gaudy collection of tacky decorations. Christmas is without its secular counterpart for the most part in Egypt, so one doesn’t walk down the street to the sound of the typical holiday tunes like one might in a mall in America. Weirdly, though, I did hear Michael Buble’s Christmas album playing in a cafe recently, so there are exceptions.

Rainy Day Alexandria

The security guards with whom I regularly exchange greetings nonchalantly hold AK-47’s and wear bulletproof vests. I’ve never felt in danger here, so I haven’t taken much notice of our security to be honest. I perceived it more as a formality than anything else. Besides, everything here has been new to me, so what’s one more thing? I didn’t take notice of the security until this week when the police parameter around all of the churches expanded. Our metal detector at St. John’s is usually located at the church gate, but now it sits outside the gate and along the compound wall several yards away. The Cathedral’s security now extends to the end of the black in each direction now, whereas it was only the church entrance that was policed. This surprised me because, like I said, I have never once felt unsafe in Egypt. I walk down the streets by myself all the time, often relying on taxis, which inevitably means I’m at the mercy of Muslim strangers on a regular basis. I know that the current President of Egypt continues to emphasize a shared Egyptian national identity between Muslims and Copts. The security guards at the churches themselves are all Muslims and pray outside the church walls they guard on rugs. They’ve been without exception kind and respectful to me. Plus, I have to appreciate their protection especially given their religion, despite what my faith teaches me about even violent self-defense (Jesus is, after all, unqualified when he says that the servant is not above the Master). I asked an Egyptian friend why the security parameter had expanded. My friend said that they do this during every holy season. I asked her how often she expects terrorist actions against Christians around Christmas and Easter. She told me that it “was not rare” and that the question they usually asked was not “when” but “where” such actions would take place this time of year. Her answer caught me off guard. This was, in part, how Egyptian Christians new that the Christmas season was here.

Christmas concern at St. John the Baptist’s, Maadi

Egypt was mostly Christian before the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century. The Arab conquests of Northern Egypt were largely made possible by the break up of a unified Christianity in Egypt after the Council of Chalcedon. The Coptic Christians have always by some other power, which has lead Christianity to develop in a way that is different from the churches of the West and East. Before the Arabs came the Copts were ruled by Greek and Roman empires. Persecution began in the third century under the reign of Diocletian, which were so violent that that time is remembered by Copts as the “Era of the Martyrs,” a remembrance beginning their liturgical year. Persecution of Coptic Christians continued under Byzantine rule in Egypt under the reigns of Marcian and Leo I in the 5th centuries. The Greeks and Romans persecute non-Chalcedonian Coptics, which weakened Christian solidarity in Egypt and so made the Muslim conquest possible that happened later.

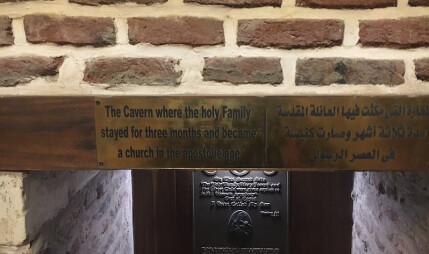

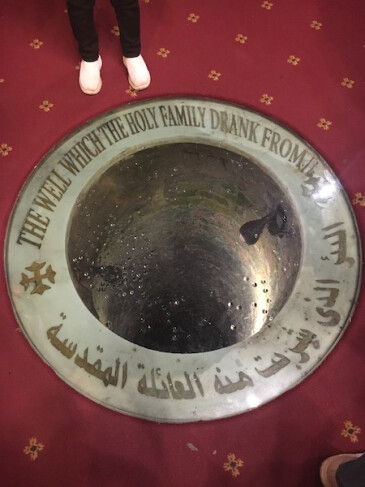

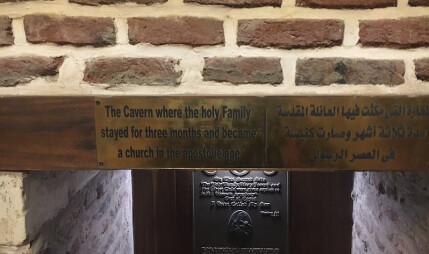

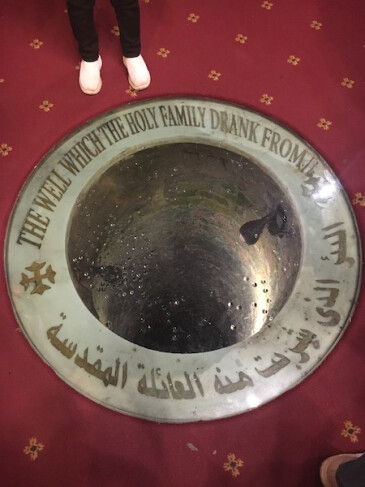

The Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus Church (Abu Serga) is built atop the cave where it is said that the Holy Family stayed during their flight to Egypt. The church also keeps a well that it is said that the holy family drank from.

It is true that the ancient Christian communities in the Near East have been coming under increasing pressure over the last several decades. Many Christians emigrate to Egypt from Syria, Iraq, and Palestine. Last week, someone seeking asylum in Egypt from Syria showed up at the Cathedral actually. He explained to a friend of mine that he has left everything: his home, his family, his religion (Islam). He has absolutely nothing, but the one thing that he does want is to become a Christian. When he arrived in Egypt he was distraught by the fact that he found not one but several churches: Coptic, Catholic, Greek, Anglican, Presbyterian, and various nondenominational congregations. This created a problem for him. He said, “I don’t have time to get on the wrong track again. I see all these churches and now I don’t know where I am supposed to go.” Yes; surely, there are many pastoral ways to respond to this, but his problem remains one that the Church has, over time, created for him and is related not just to schism but its violent legacy as well.

Altar at St. Mark’s Pro Cathedral, Alexandria.

Church unity has to be found in our own, Episcopal home before other, shameful divisions can be recognized, healed, and overcome between the Churches. Catholicity isn’t an intellectual issue or a reality entertained only be priests and bishops. This asylum-seeker is not only looking for a safe country in which to live, but a Christian home, which our ecclesial marketplace has made confusing and difficult. Some might say that “these divisions have nothing to do with me,” but the dead are not coming back to take responsibility for their actions; rather, we are the generation now that can claim responsibility for our, shared ecclesial sins. There is an analogy here to the way many whites the U.S. have responded to renewed calls for ethnic unity and an end to racism in America. Some whites protest: “I didn’t do it. That was a long time ago, so I’m not responsive for the violence they did.” Such locutions are used to suggest that “I” am not affiliated with any shared, generational past and consequently should not be asked to responsible for the legacy of that violence that continued to be felt in the here and now by our black neighbors. This is one way of denying what Scripture says sin often is: generational. Perhaps America is simply too diffuse of a public for whites to be corporately enjoined to a history such that their identification with and confession of past sins could genuinely be more than a kind of vain virtue signaling. However, the Church is not a diffuse a “public,” but a Body, the single Body of Christ, which more intimately connects us historically and morally to the ongoing sinful and even murderous diffusion of our essential catholicity. In other words, that the Church is a communion consisting of the living and the dead is morally and not just spiritually commanding.

Clergy meeting

Much is made of the Church’s dead, however, what is often missed is our linkage with the Christian dead who we do not want to call “saints” and those that we wish were not so designated, those that seem to be counter-images of Christ, like Judas, our betraying brother, who sat and ate with us and Him, too. The shape of Christian witness is that of an obedient and compassionate suffering. Such a witness today might look like a humble one that does not merely enter into “ecumenical dialog,” but willingly account for its past failures, those that continue to strand us on opposing ecclesial shores, such as this asylum-seeker. Christmas is, of course, not potentially dangerous in Egypt because of Christian schism. But, surely, we are to be the place where Mary’s song, attesting to the generation’s of blessing that are to be found in her child, can be recognizably not just be heard but tangibly seen and felt.

Pray for my Christian brothers and sisters here in Egypt as they get ready for Christmas. People are joyful and unafraid, but there is some risk. And, pray for the Church, our unity, such that all stumbling blocks would be removed from those that are drawn to her, seeking the Christ.

The seal for the new diocese of Gambella and the seal of the Episcopal-Anglican Province of Alexandria

Prayers:

- Continued prayers for peace in Ethiopia and for protection of the Churches there

- Prayers for protection for all Christians in Egypt during this holiday season

- Continued prayers for the future of my vocation in the Province and thanksgiving for all that I have received from the Christians of Egypt and the Horn of Africa so Far

OTHER WAYS YOU CAN HELP:

- Well Project (Gambella): Clean drinking water is a very serious need in Gambella. The Anglican Church hopes to begin a water ministry at Good Shepherd Cathedral, which is located on the outskirts of town and has no running water or electricity. This ministry would provide clean drinking water to the community around the Cathedral, but we need a lot of financial help to make this happen. A little goes a long way. If you’d like to understand the cost breakdown of this project, click here. To donate to this project, click here.