You Are Called: Week One

Sunday 9 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

The Cloud of Unknowing is an anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century. The text is a spiritual guide on contemplative prayer in the late Middle Ages. The book counsels a young student to seek God, not through knowledge of the mind, but through intense contemplation, motivated by love, and stripped of all thought.

Anonymous, The Cloud of Unknowing, Chapter 3

How the work of contemplation shall be done; of its excellence over all other works.

This is what you are to do: lift your heart up to the Lord, with a gentle stirring of love desiring him for his own sake and not for his gifts. Center all your attention and desire on him and let this be the sole concern of your mind and heart. Do all in your power to forget everything else, keeping your thoughts and desires free from involvement with any of God’s creatures or their affairs whether in general or in particular. Perhaps this will seem like an irresponsible attitude, but I tell you, let them all be; pay no attention to them.

What I am describing here is the contemplative work of the spirit. It is this which gives God the greatest delight. For when you fix your love on him, forgetting all else, the saints and angels rejoice and hasten to assist you in every way—though the devils will rage and ceaselessly conspire to thwart you. Your fellow men are marvelously enriched by this work of yours, even if you may not fully understand how; the souls in purgatory are touched, for their suffering is eased by the effects of this work; and, of course, your own spirit is purified and strengthened by this contemplative work more than by all others put together. Yet for all this, when God’s grace arouses you to enthusiasm, it becomes the lightest sort of work there is and one most willingly done. Without his grace, however, it is very difficult and almost, I should say, quite beyond you.

And so diligently persevere until you feel joy in it. For in the beginning it is usual to feel nothing but a kind of darkness about your mind, or as it were, a cloud of unknowing. You will seem to know nothing and to feel nothing except a naked intent toward God in the depths of your being. Try as you might, this darkness and this cloud will remain between you and your God. You will feel frustrated, for your mind will be unable to grasp him, and your heart will not relish the delight of his love. But learn to be at home in this darkness. Return to it as often as you can, letting your spirit cry out to him whom you love. For if, in this life, you hope to feel and see God as he is in himself it must be within this darkness and this cloud. But is you strive to fix your love on him forgetting all else, which is the work of contemplation I have urged you to begin, I am confident that God in his goodness will bring you to a deep experience of himself.

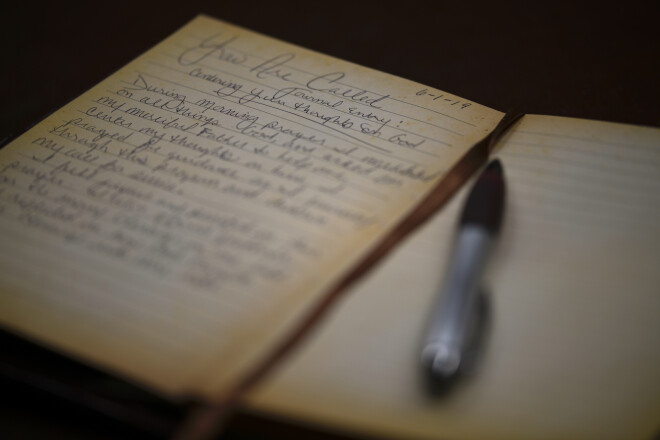

Daily journaling

Center your thoughts on God.

Monday 10 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

The expansion of factories and industry in the nineteenth century created a class of wealthy owners, a class of industrial workers, and a host of new social problems. Socialists proposed that the state should take over the factories from private ownership. In this official papal statement, Leo XIII (1810-1903, pope from 1878 until his death) sought a middle ground, recognizing the oppression workers could suffer but rejecting the abolition of private property as a solution. In the Catholic tradition, Leo thinks of a job primarily as a way to support one’s family, not as a calling in itself. “Rerum Novarum” (“New things”) is conservative on issues of the father’s place in the family, but it was and is radical on issues of labor and capital.[1]

Pope Leo XIII, “Rerum Novarum,” The Papal Encyclicals 1878-1903

But the Church, with Jesus Christ as her Master and Guide, aims higher still. She lays down precepts yet more perfect, and tries to bind class to class in friendliness and good feeling. The things of earth cannot be understood or valued aright without taking into consideration the life to come, the life that will know no death. Exclude the idea of futurity, and forthwith the very notion of what is good and right would perish; nay, the whole scheme of the universe would become a dark and unfathomable mystery. The great truth which we learn from nature herself is also the grand Christian dogma on which religion rests as on its foundation—that, when we have given up this present life, then shall we really begin to live. God has not created us for the perishable and transitory things of earth, but for things heavenly and everlasting; He has given us this world as a place of exile, and not as our abiding place. As for riches and the other things which men call good and desirable, whether we have them in abundance, or are lacking in them—so far as eternal happiness is concerned—it makes no difference; the only important thing is to use them aright. Jesus Christ, when He redeemed us with plentiful redemption, took not away the pains and sorrows which in such large proportion are woven together in the web of our mortal life. He transformed them into motives of virtue and occasions of merit; and no man can hope for eternal reward unless he follow in the blood-stained footprints of his Savior. “If we suffer with Him, we shall also reign with Him” (Rom. 8:17). Christ’s labors and sufferings, accepted of His own free will, have marvelously sweetened all suffering and all labor. And not only by His example, but by His grace and by the hope held forth of everlasting recompense, has He made pain and grief more easy to endure; “for that which is at present momentary and light of our tribulation, worketh for us above measure exceedingly an eternal weight of glory” (2 Cor. 4:17).

It rests on the principle that it is one thing to have a right to the possession of money and another to have a right to use money as one wills. Private ownership, as we have seen, is the natural right of man, and to exercise that right especially as members of society, is not only lawful, but absolutely necessary. “It is lawful,” says St. Thomas Aquinas, “for a man to hold private property; and it is also necessary for the carrying on of human existence.” But if the question be asked; How must one’s possession be used?—the Church replies without hesitation in the words of the same holy Doctor; “Man should not consider his material possessions as his own, but as common to all, so as to share them without hesitation when others are in need. Whence the apostle saith, ‘Command the rich of this world….to offer with no stint, to apportion largely’” (1Tim. 6:17-18). To sum up, then, what has been said; Whoever has received from the divine bounty a large share of temporal blessings, whether they be external and material, or gifts of the mind, has received them for the purpose of using them for the perfecting of his own nature, and, at the same time, that he may employ them, as the steward of God’s providence, for the benefit of others.

As for those who posses not the gifts of fortune, they are taught by the Church that in God’s sight poverty is no disgrace, and that there is nothing to be ashamed of in earning their bread by labor. This is enforced by what we see in Christ Himself, who, “whereas He was rich, for our sakes became poor’ (2 Cor. 8:9); and who, being the Son of God, and God Himself, chose to seem and to be considered the son of a carpenter—nay, did not disdain to spend a great part of His life as a carpenter Himself. “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary?” (Mark 6:3)[2]

Daily Journaling

The gift of work

Tuesday 11 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

Thomas Merton (1915-1968) grew up, the son of an artist, in France, England, and the United States. After studying at Columbia University in New York, he was writing poetry and very much living the life of a young bohemian until his conversion to Catholicism in 1938. In 1941, he joined the Trappist monastery at Gethsemani in Kentucky. Dedicated to a life of silence, the Trappists, an offshoot of the Cistercian order, are perhaps that most rigorous of monastic orders today. Merton’s autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1948, became a best-seller, and he continued to write poems and essays, attacking racism, poverty, and nuclear armament as well as discussing the spiritual life. He died in Bangkok, where he had gone to a meeting between Catholic and Buddhist monks.[3]

Thomas Merton, No Man is an Island

Each one of us has some kind of vocation. We are all called by God to share in His life and in His Kingdom, Each one of us is called to a special place in the Kingdom. If we find that place we will be happy. If we do not find it, we can never be completely happy. For each one of us, there is only one thing necessary: to fulfill our own destiny, according to God’s will, to be what God wants us to be.

We must not imagine that we discover this destiny only by a game of hide-and-seek with Divine Providence. Our vocation is not a sphinx’s riddle which we must solve in one guess or else perish. Some people find, in the end, that they have made many wrong guesses and that their paradoxical vocation is to go through life guessing wrong. It takes them a long time to find out that they are happier that way.

Our vocation is not a supernatural lottery but the interaction of two freedoms, and therefore, of two loves. It is hopeless to try to settle the problem of vocation outside the context of friendship and of love. We speak of Providence: that is a philosophical term. The Bible speaks of our Father in Heaven. Providence is, consequently, more than an institution, it is a person. More than a benevolent stranger, He is our Father. And even the term “Father” is too loose a metaphor to contain all the depths of the mystery: for He loves us more than we love ourselves, as if we were Himself. He loves us, moreover, with our own wills, with our own decisions. How can we understand the mystery of our union with God Who is closer to us than we are to ourselves? It is His very closeness that makes it difficult for us to think of Him. He Who is infinitely above us, infinitely different from ourselves, infinitely “other” than we, nevertheless dwells in our souls, watches over every movement of our life with as much love as if we were His own self. His love is at work bringing good out of all our mistakes and defeating even our sins.

In planning the course of our lives, we must remember the importance and the dignity of our own freedom. A man who fears to settle his future by a good act of his own free choice does not understand the love of God. For our freedom is a gift God has given us in order that He may be able to love us more perfectly, and be love by us more perfectly in return.

There is something in the depths of our being that hungers for wholeness and finality. Because we are made for eternal life, we are made for an act that gathers up all the powers and capacities of our being and offers them simultaneously and forever to God. The blind spiritual instinct that tells us obscurely that our own lives have a particular importance and purpose, and which urges us to find out our vocation, seeks in do doing to bring us to a decision that will dedicate our lives irrevocable to their true purpose.[4]

Daily Journaling

God’s gift of freedom

Wednesday 12 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) grew up in a prosperous Danish family and was preparing to get married and studying for ordination as a Lutheran pastor. But he felt himself called to be a kind of Christian Socrates. Just as Socrates had challenged Athenians to realize how little they knew, so Kierkegaard challenged Danish Christians to realize how little faith they had. He faced, he wrote, the particularly difficult task of introducing real Christianity into a country where everyone thought they were already Christians—but they were far too comfortable, they thought faith far too easy. He wrote a series of books; Fear and Trembling appeared as written by “Johannes de Silentio.” Johannes admits that he is not a Christian; he lacks faith. But, reading the story in Genesis 22 of how God called Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac, Johannes at least recognizes that Abraham’s kind of faith is an amazing thing, far beyond what he can understand. Faith—a faith that goes beyond resignation in the face of life’s tragedies and may challenge basic ethical principles—may be the highest vocation of all.[5]

Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling

By faith Abraham emigrated from the land of his fathers and became an alien in the promised land. He left one thing behind, took one thing along: he left behind his worldly understanding, and he took along his faith. Otherwise he certainly would not have emigrated but surely would have considered it unreasonable. By faith he was an alien in the promised land, and there was nothing that reminded him of what he cherished, but everything by its newness tempted his soul to sorrowful longing. And yet he was God’s chosen one in whom the Lord was well pleased! As a matter of fact, if he had been an exile, banished from God’s grace, he could have better understood it—but now it was as if he and his faith were being mocked. There was also in the world one who lived in exile from the native land he loved. He is not forgotten, nor are his dirges of lamentation when he sorrowfully sought and found what was lost. There is no dirge by Abraham. It is human to lament, human to weep with one who weeps, but it is greater to have faith, more blessed to contemplate the man of faith.

By faith he received the promise that in his seed all the generation of the earth would be blessed. Time passes, the possibility was there, Abraham had faith; time passed, it became unreasonable, Abraham had faith. ….We have no dirge of sorrow by Abraham. As time passed, he did not gloomily count the days; he did not stop the course of the sun so she would not become old and along with her his expectancy; he did not soothingly sing his mournful lay for Sarah. Abraham became old, Sarah the object of mockery in the land, and yet he was God’s chosen one and heir to the promise that in his seed all the generations of the earth would be blessed.

But Abraham had faith and did not doubt; he believed the preposterous. If Abraham had doubted, then he would have done something else, something great and glorious, for how could Abraham do anything else but what is great and glorious! He would have gone to Mount Moriah, he would have split the firewood, lit the fire, drawn the knife. He would have cried out to God, “Reject not this sacrifice; it is notthe best that I have, that I know very well, for what is an old man compared with the child of promise, but it is the best I can give you. Let Isaac never find this out so that he may take comfort in his youth.” He would have thrust the knife into his own breast. He would have been admired in the world, and his name would never be forgotten; but it is one thing to be admired and another to become a guiding star that saves the anguished. [6]

Daily Journaling

God provides

Thursday 13 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

Gordon T. Smith, The Voice of Jesus

Spiritual discernment is an intentional way by which we respond with courage and integrity to our world. Discernment enables us both to see the world more clearly and to respond well to what we see. We discern our circumstances; we then, in turn, discern the appropriate response.

This discernment includes the capacity to know one’s vocation, or how one is being called, at this time and in this place, to give of one’s energies, whether that is in a career or in volunteer service. It also involves moral discernment—the capacity to see how one should respond in love and justice to a moral dilemma. Both have to do with discerning how we act in the world, in response to the call of Christ. And in both cases we are being called to offer not a vague, general response to God but a specific response to whom we are being called to be at this time and place.

What this means for the Christian believer is that vocational discernment intersects our lives at regular intervals. It is not now (if it ever was) a spiritual exercise merely for the young person who is trying to choose a career. The task of discerning vocation is fundamental for anyone who wishes to live with personal integrity, courage, and authenticity. We come up against the challenge of vocational discernment again and again and again. …Nothing is routine other than the reality that at frequent intervals we are challenged with discerning vocation—who am I and to what am I being called? And when we face these passages, what we long for is to hear the voice of Jesus.

Further, there is a sense in which part of Christian discipleship is accepting with grace that we each have a cross to bear. This is not some kind of martyr complex or masochism. Rather, it is an acknowledgment that in our calling we identify with the suffering of Christ. The brokenness of the world inevitably impacts our lives, and so our work will, in either an obvious or more subtle way, be a mysterious means by which we identify with Christ and his work (Rom 8:17).

But though we are called to bear the cross, we are certainly not called to bear each and every cross! Jesus, in the last moments before his Passion, probably had a keen awareness of the cross he was facing. Nevertheless there, in the Garden of Gethsemane, he discerned with certainty that he was to accept the horror and humiliation of crucifixion and the abuse of the religious and political leaders of his day. And in our identification with him, while we may not have a Gethsemane counterpart, our discernment will often include an awareness of the cross that we are, or may be, called to bear.[7]

Daily Journaling

Identifying with Christ’s Passion

Friday 14 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

Francis of Assisi (1181-1226), the son of an Italian merchant, found himself called to a life of radical poverty and service. When others sought to follow him, he obtained the permission of Pope Innocent III to found a new order, eventually called the Franciscans. Bonaventure (about 1217-1274) joined the Franciscan order less than twenty years after Francis’s death and became one of the great theologians of his time. His biography of Francis came to be the official account of the saint’s life.[8]

Up to this time, however, Francis was ignorant of God’s plan for him. He was distracted by the external affairs of his father’s business and drawn down toward earthly things by the corruption of human nature. As a result, he had not yet learned how to contemplate the things of heaven nor had he acquired a taste for the things of God. Since affliction can enlighten our spiritual awareness (Isa. 28:19), the hand of the Lord came upon him (Ezek. 1:3) and the right hand of God effected a change in him (Ps. 76:11), God afflicted his body with a prolonged illness in order to prepare his soul for the anointing of the Holy Spirit. After his strength was restored, when he had dressed as usual in his fine clothes, he met a certain knight who was of noble birth, but poor and badly clothed. Moved to compassion for his poverty, Francis took off his own garments and clothed the man on the spot. At one and the same time he fulfilled the two-fold duty of covering over the embarrassment of a noble knight and relieving the poverty of a poor man.

The following night, when he had fallen asleep, God in his goodness showed him a large and splendid palace full of military weapons emblazoned with the insignia of Christ’s cross. Thus God vividly indicated that the compassion he had exhibited toward the poor knight for love of the supreme King would be repaid with an incomparable reward. And so when Francis asked to whom these belonged, he received an answer from heaven that all these things were for him and his knights. When he awoke in the morning, he judged the strange vision to be an indication that he would have great prosperity; for he had no experience in interpreting divine mysteries nor did he know how to pass through visible images to grasp the invisible truth beyond. Therefore, still ignorant of God’s plan, he decided to join a certain count in Apulia, hoping in his service to obtain the glory of knighthood, as his vision seemed to foretell.

He set out on his journey shortly afterwards; but when he had gone as far as the next town, he heard during the night the Lord address him in a familiar way, saying: “Francis, who can do more for you, a lord or a servant, a rich man or a poor man?” When Francis replied that a lord and a rich man could do more, he was at once asked: “Why then, are you abandoning the Lord for a servant and the rich God for a poor man?” And Francis replied: “Lord, what will you have me do?” (Acts 9:6). And the Lord answered him: “Return to your own land (Gen. 32:9), because the vision which you have seen foretells a spiritual outcome which will be accomplished in you not by human but by divine planning.” In the morning (John 21:4), then, he returned in haste to Assisi, joyous and free of care; already a model of obedience, he awaited the Lord’s will.[9]

Daily Journaling

Waiting for God’s will

Saturday 15 June 2019

Prayer

Most powerful Holy Spirit, come down upon us and subdue us. From heaven, where the ordinary is made glorious, and glory seems but ordinary, bathe us with the brilliance of your light like dew. Amen

Reflection

St. John of the Cross, Juan de Ypes y Alvarez, was born in 1542 of Jewish ancestry, in the town of Fontiveros near Avila, Spain. He died, aged 49, in 1591. He was ordained a priest in 1567. Soon after that he met St. Teresa of Avila who persuaded him to join her in the reform of the Carmelites. ….St. John of the Cross seems to have found his inspiration for his teachings on mystical theology from his own experience. He knew the Scriptures by heart and was well versed in the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas. …He teaches, evidently from his own experience, that the soul must empty itself of itself in order to be filled with God.

St. John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul

By way of love this dark contemplation infuses into the soul a secret, dark wisdom. It is called secret and dark because it is not known to the intellect or our other faculties. This wisdom cannot be fathomed by the intellect or the world or the flesh or the devil since it is given directly by God. Thus it is protected from them all. This contemplation, or wisdom of love, communicates an illumination which is ineffable. The soul cannot adequately express it or describe it or communicate it in any way.

It is beyond the ability of the imaginative faculty to deal with it. It is so spiritual and intimate to the soul that it transcends everything sensory and even the ability of the exterior and interior senses. This results in the soul being so elevated and exalted that it sees every created thing as deficient and inadequate in dealing with this divine experience. The soul has been brought into the realm of mystical theology which is essentially dark and secret to all of its faculties and natural capacity.

This secret wisdom is like a ladder which the soul climbs to get to the treasures of heaven. Like a ladder it goes up and down, up to God and down to self-humiliation. According to Proverbs the soul is humbled before it is exalted and it is exalted before it is humbled. Tempests and trials usually follow prosperity. Abundance and peace succeed misery and torment. Perfect love of God and contempt of self cannot exist without knowledge of God and knowledge of self. The former is exultation; the latter is humility. Like a ladder, or step by step, this secret knowledge both illumines and enamors the soul raising it up to God. [10]

Daily Journaling

Knowledge of God and self

[1]William C. Placher, Callings, Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Erdmans Publishing Co., 2005), pp. 359-360.

[2]Pope Leo XIII, “Rerum Novarum,” The Papal Encyclicals 1878-1903, ed. Claudia Carlen Ihm (Raleigh, N. C.: McGrath, 1981) 241-47, 251-53.

[3]William C. Placher, Callings, Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Erdmans Publishing Co., 2005), p. 421.

[4]Thomas Merton, No Man Is an Island(New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1955), 131-33, 140-48, 152-57.

[5]William C. Placher, Callings, Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Erdmans Publishing Co., 2005), p. 333.

[6]Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 17-21, 28-30, 32-33, 37-41.

[7]Gordon T. Smith, The Voice of Jesus; Discernment, Prayer and the Witness of the Spirit (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2003), pp. 183, 185, 186.

[8]William C. Placher, Callings, Twenty Centuries of Christian Wisdom on Vocation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Erdmans Publishing Co., 2005), p. 143.

[9]Bonaventure, The Life of St. Francis, trans. Ewert Cousins (Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist, 1978), 186-88.

[10]William Meninger, OCSO; St. John of the Cross (New York: Lantern Books, 2014), pp. 185-187.