Boomer-ology

As you may know, there is a debate anew about a revision of the BCP in the Episcopal Church. I think it's ill-conceived theologically, and we as a church have other fish we'd better get on with frying! But there is another interesting issue one often hears about, which I want to focus on here, a generational one. Basically, the revision is so very boomer, and we the soon-to-retire are out of touch and need to let it go. It's interesting since we imagine it to be the opposite, but that's rather boomer too, isn't it?

What is the evidence? First, there are younger Episcopalians who may be more progressive than I on social issues, but don't want revision either. A more traditional kind of worship is what attracted them. In addition to this evidence from the pews, there is evidence from the world of theology. The revisionists who mutter about softening atonement language failed to get the memo about the enormous popularity of a scholar like Rene Girard. Third, and finally, we can learn from sociology. A scholar like Mary Douglas taught us that incessant revision is not a sign of enlightenment but only of a rootless, mobile, commodified, spiritual equivalent of constantly rearranging your furniture.

The job of the aging is to move over gracefully, the one thing which proves so hard for us Boomers.

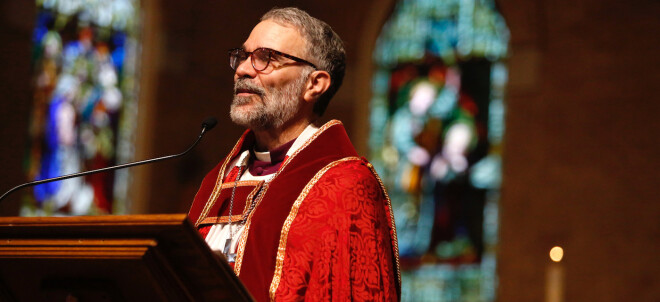

Peace,

+GRS