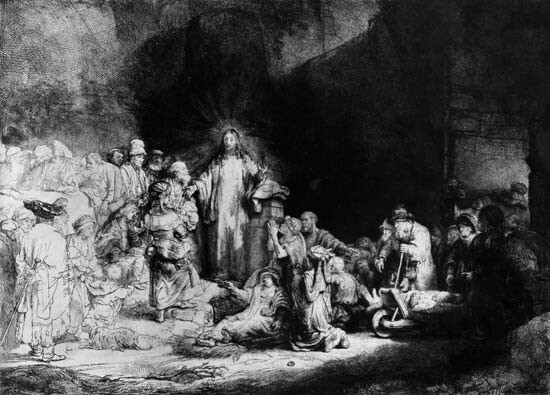

There are words in the Bible that are far from our daily experience, and sacrifice is one of them. Maybe we say “he had to sacrifice a lot to get where he is,” but even that is a far cry from cutting the throats of chickens under a tree and pouring out the blood in the name of some god, as would happen in Africa when Stephanie and I were there. But that kind of practice is not far from the writers of the Bible, and of course they themselves slaughtered animals for the sake of the God of Israel, with the blood running down the altar in rivers. What is all that about? Why have humans all around the world done such things? Often we think that the point was putting our wrong off on the poor animal, and that was doubtless so in many cases, but I want to look at another aspect- life, access to it, in its abundance and power. That is what the sacrificer wanted, and we too, if we are honest.

Let me offer a good Texas example. The wildcatter searches, drills, looking for the vein, the sluice, the gusher. And when he finds it, it is not his doing, it was already there, and finding it means for him, the means of life, sometimes extravagantly. Well that is how ancient people thought of sacrifice- opening up a vein of life, like the vein of a ram, so that an outpouring would follow. And what would the enterprising wildcatter then do? Build a rig, a framework, not to create life, not even to control it really, but to allow them to live and work around it, so that they could live off its benefits.

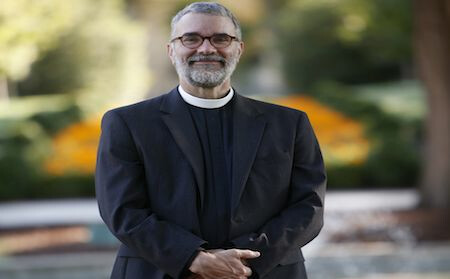

The Bible thinks about sacrifice in a very particular way, and so we need to do the same. Trying to make sacrifice yourself, trying to accomplish salvation on your own, is doomed. You are not the sacrifice. Some people take their whole life trying to learn that lesson and fail. But there is a sacrifice, sufficient, a great one, the great opening of life to every human being, to the world, and it is the death and resurrection of the anointed one, Jesus. Out of him flows the river of life Revelation speaks of. Everything you read in the Old Testament predicts and prepares for the great geyser. Everything we do here in the pulpit and the altar reminds and presents the fact of the one great sacrifice. It is one long history focused on the river of life that flows out of the side of the broken, sacrificed body of God’s Son. That is the Gospel in short form: no sacrifice in us, one sacrifice in Him, the temple of Zion pointing to it and the sacraments pointing back. And that includes, I might this evening add, your priest, Craig serving in your midst to be a living pointer back to the sluice, a kind of breathing divining rod for the stream of life. He has done, and will do a hundred things in ministry at Holy Cross, Paris, but see this evening how he is here, amidst it all, to do one thing, the help build and maintain the scaffolding over the gusher, to keep pointing out where the well is found, out of the dying side of Jesus on the holy cross. And when he does that, you and I find there rest for our soul and life that these dying bodies of our cannot on their own achieve.

But what about us? This is where this evening’s epistle reading comes into play. In the epistle to the Romans, Paul presents the news of river of life, the death and resurrection of Jesus. And he lays out the case about how we can’t create our own stream- he calls it the “justification by God of us sinners.” Now he gets practical in chapter 12- how does this spiritual geology actually work in quenching thirst. What kind of a rig does an individual build over the gusher? Listen to what he says: “by the mercies of God present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God, which is your reasonable service.” That last word could also be translated “worship.” The prayer book picks up the theme when it says we, who can offer no sufficient sacrifice of our own, who worship the sacrifice of Jesus, are supposed to offer a “sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving.” Wait a minute- on the one hand, no sacrifice, and on the other, we are to offer a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving. The answer is this. We are not the sluice. But we do need a scaffold over it to make it central in our lives. We need to give it the praise it deserves. We need to align our lives in gratitude, we need to realize that the river of life is at the center of the world, that loving self-sacrifice for the sake of life is who God is, and then imitate, humbly, ever so partially, the shape of God’s own way with the world.

But what does this sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving look like? What in other words does your Christian life look like? First it is by the mercies of God- you are dependent, a learner, Jesus says like a child. Second of all you are to present your body. This means all of our life- your thoughts, actions, showing up, suffering, self-denial sometimes, generosity others, saying your sorry, seeing how fragile life is- all that in the light of God who is a river of eternal life. And only in this sense are you to be a living sacrifice- a scaffold marking the spot. You are to be holy, that means, not a claim you are better than others, but rather that God has reached out and made a claim on you to be a sign of Him, the way a ram or goat was chosen for the temple. And Craig, also set apart, is here to remind you of the divine claim, on days you want to remember and days you wish you could act as you wish. Acceptable to God- because you are following in the tracks of Jesus, in whom his heavenly father was well pleased. Next he says to make your doing a kind of liturgy, a collective act of praise, what Mother Teresa called “something beautiful for God,” not just in your acting but in how you think and speak and even how you remember the past, all of that turned over to Him because he has the words of life, the river without which we perish.

Let’s shift our perspective slightly and think about where a sacrifice is offered, namely a Temple. The human heart is built to seek out Bethel- the house of God, the spot where the fountain flows. Israel named that spot dedicated to God Zion. Your church makes the claim that that spot is really the cross of Jesus. Your building is really a symbol of you, for you are the stones, Peter tells us, where the sacrifice is made, by which he means proclaiming in word and example, in the building and outside it, the Son of God. Humans need a temple because they need access to life, they need to live at the font of sacrifice.

And what is the Temple for us now? As I mentioned, Peter in his first letter gives us the answer, as he quotes the book of Genesis: you are ‘living stones, built up as a spiritual house, a holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices.’ The reminder of the true temple, the replica, is us. I heard recently of an African American church in Dallas, which was renovated, but in such a way not to replace any of its bricks, which had been brought by its members bit by bit over many years to build the edifice as they went- they brought bricks who were its bricks. And our own bodies are replicas of a Temple, one that offers praise and thanksgiving, one that is eventually broken down so that it can some day be rebuilt. That is our real purpose from God- to become temples, as Paul says, of the Holy Spirit.

It is in this spirit that we can read the poem by the great Anglican poet of the 17th Century, the priest George Herbert. He chose to minister in a rural church, pouring himself into its life. In the poem he asks them to see their lives as a Temple, and they church building itself as an image of their lives. Make your life like Holy Cross, each virtue a stone on the way to the altar of God , each crack a struggle or failing in our lives, the stains the hardships through which we are wayfarers on the way to God. See in this church your lives, see in your lives a church built toward God. Then he looks up to the stained glass. There the word of God you hear in this place is like a colored pane of glass through which the events of life look different, can be seen as indicative of something higher and deeper.

All this brings us around to Craig, whose ministry among us we give thanks for and pray for this evening. His preaching is just such a colored glass through which we see our lives in relation to the God of eternity. He is a stone in this temple. The purpose and discipline of his life are the scaffolding that sustain him at the edge of the waters of flowing life. He teaches us to understand ourselves as placed here for the purpose of the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving. He will be a godly example of working the day-to-day details of the sacrificial life, the life of abundant life in Jesus Christ in joy and sorrow. For all that we with enthusiasm, this evening, say Amen.