Hiding Baby Jesus

I have a friend who, when he was a young boy, learned that Baby Jesus was not supposed to be in the creche before Christmas Eve. My friend got the point: Baby Jesus goes into the creche at Christmas, and not before.

But he was very young. So when his family visited other homes in the weeks leading up to Christmas, if he saw Baby Jesus in a creche, he just took him out and hid him somewhere in the house. He didn’t tell anyone that he was doing it, and he didn’t tell them where Jesus had been hidden. He just knew Jesus needed to hide away until Christmas.

---

The stories here start to multiply. In one home, Baby Jesus was never found, not that Christmas, not at a future Christmas, not even when the residents had moved out and died. In this case, Jesus was hidden for good.

In another, the creche figures had been made out of some sort of dough, baked and then painted. This hidden Jesus was sniffed out by the house canine, who enjoyed a small bite and some chewing (but left enough for the corpse to be identified).

---

I’m reminded of the best nearly-unknown novel of the last century, J. F. Powers’s Morte d’Urban. Powers wrote finely-grained, deadpan hilarious stories of Roman Catholic clergy life. At one point in this novel—which won the National Book Award in 1963—Baby Jesus disappears from the creche, and Father Urban knows who did it: that new priest in the rectory. (I’ll stop there because you have to read it to get it.) (Which I recommend, that is, getting it to read it.)

What my friend did as a very young lad was both wrong and right: wrong, to mess around with creches without talking it through, yet right, to see that the Christmas story has built into it the tension of delay. The Word was hidden away—God had never been seen in the world—and then, on Christmas, he appeared for our adoration and salvation.

And despite that, we can hide him away and thwart his appearing. He can be buried in our home and never seen. He can be, as it were, turned over to the dogs.

Christians need both to wait for Jesus and not to hide him.

---

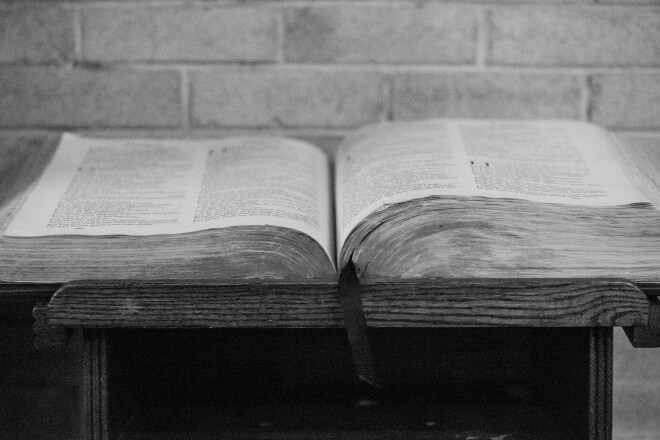

Out & About. On Sunday, January 14, I will start a multi-week Sunday class on the Song of Songs. In Losing Susan I have claimed that this is the second-best book of the Bible, yet it is notoriously ignored today. The class will be at 9:30 a.m. at St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Dallas.

My sermon on December 31 at Incarnation in Dallas will be posted here.

On the Web. I review David Bentley Hart’s new translation of the New Testament in the January issue of The New Criterion. If you can get behind the paywall, you will see that my review is mixed.